Become a Member of the International Association of the Fantastic in the Arts

JFA Presents – Yemoja’s Tears: Bodies, Water and Bodies of Water – Table of Contents

Preface

Novella Brooks de Vita and Cat Ashton

Introduction: A Water Scarcity Awareness and Alleviation Anthology

Alexis Brooks de Vita

Source

Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki

Doomed to the Storm

Mame Bougouma Diene

Stone Bridge and Laughter

Alex Jennings

GodIsLove: Signified Sankofarrations, Personified Deities, and Mythatypical Patterns in The Joys of Motherhood and Freshwater

Candice Thornton

Emerging

Joyce Chng

A Pocketful of Precious

Annette Meserve

Whose Water Is It, Anyway?

Eileen Gunn

Bayelsa, Water for All

Solomon Uhiara

Miriam After the Flood

F. Brett Cox

The Revenge of Yemoja

Wuraola Kayode

Water Guzzlers and Time Wasters

Gillian Polack

Quizani and the Eagle/Quizani y el Águila (English/Spanish)

Alfonso Arteaga Rodríguez/Alfonso Arteaga

The Ship of Sisyphus

James Morrow

Ocean Scourge

A.E. Fonsworth

Inmates of Ikenga Point

Uchechukwu Nwaka

Fanon and Soyinka on Traditional African Ecoharmony, Colonial Greed, and the Mystic Functionality of Water

Mingle Moore, Jr.

The Turning Part

Virgília Ferrão

Laundry

Regina M. Hansen

le mot, la mort

Albert Uriah Turner, Jr.

Stalwart

MultiMind

Finding Water to Fish with Friends and Family: Daybreak

James H. Ford, Jr.

Water Is Life, Water Is Death, There Is No Truth or Joy Without Water

Mary A. Turzillo

Love, Temptation and the Downfall of a Water Rig in Kai Ashante Wilson’s “The Devil in America”

Desireé Y. Amboree

The Weird Sisters of Onapatu Bog

Ceschino

Water for Tears

Lakunle Whesu

A Dry Death

Vuyokazi Ngemntu

Abstract

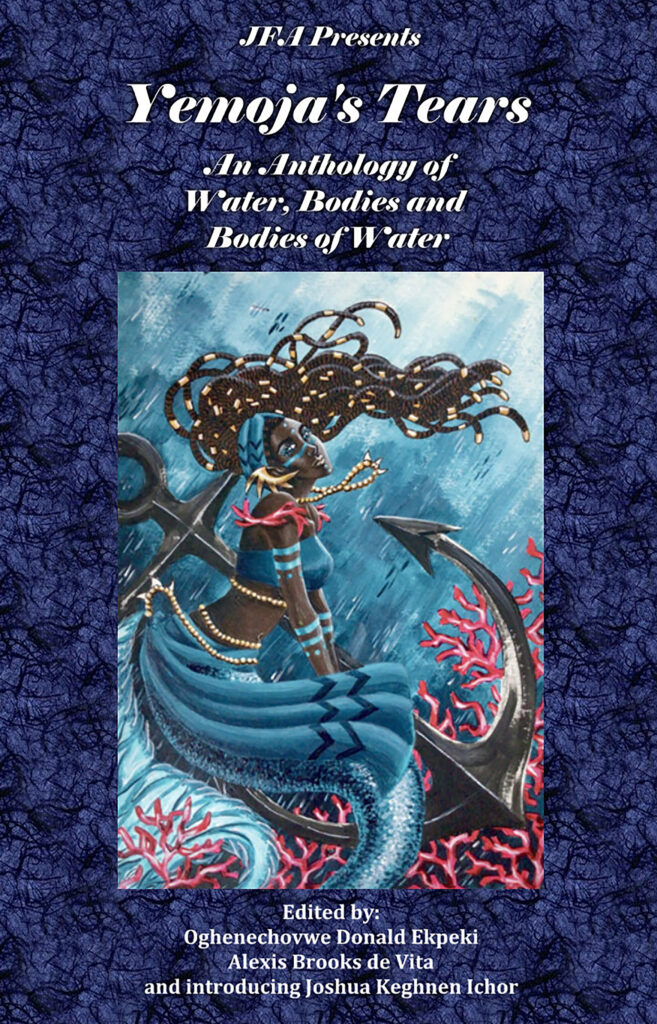

The Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts presents Yemoja’s Tears: An Anthology of Water, Bodies and Bodies of Water, a creative and analytical project to raise awareness and funds for water safety engineering throughout vulnerable communities in Nigeria and the African Continent. This anthology features editors Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki and Alexis Brooks de Vita and introducing Joshua Ichor Keghnen in a collection of stories, poetry and analysis by Mame Bougouma Diene, Alex Jennings, Candice Thornton, Joyce Chng, Annette Meserve, Eileen Gunn, Solomon Uhiara, F. Brett Cox, Wuraola Kayode, Gillian Polack, Alfonso Arteaga Rodriguez, James Morrow, A.E. Fonsworth, Uchechukwu Nwaka, Mingle Moore, Jr., Virgilia Ferrao, Regina M. Hansen, Albert Uriah Turner, Jr., MultiMind, James H. Ford, Jr., Mary A. Turzillo, Desiree Y. Amboree, Ceschino, Lakunle Whesu and Vuyokazi Ngemntu.

[Preface]

THE CREATIVE AND SCHOLARLY CONTRIBUTIONS in this anthology immerse the reader in water awareness. Authors have contributed their thoughts and dreams about water: its availability and scarcity, its precariousness and its resilience, its generous ability to heal and its fragile inability to wash away inhumanity or greed. Immersion in this anthology inspires each of us to see ourselves, both individually in our aloneness and collectively as a water activist community, as the solutions we can be to solve the multiplicity of problems stemming from clean water scarcity, worldwide.

From the time that Joshua Keghnen Ichor and Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki approached the Editors-in-Chief of the Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts with a proposal for an anthology project to raise awareness and funds for water safety engineering throughout vulnerable communities in Nigeria and the African Continent, months were spent exploring potential charitable hosts for this innovative enterprise. But, as short stories, memoirs, essays, and poetry were donated to this anthology project, and while the fame of and interest in the GeoTek Monitor is widespread and growing, our fundraising goals were generally considered too small-scale for the hosting we pursued. We took the time to get expert and legal advice on how best to direct funds raised to provide communities with water while maintaining transparency. That did take more time than we initially expected, but we felt it was important not to risk legal missteps or misperceptions in the handling of charitable funds, if they could be foreseen and avoided.

While the Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts is sponsoring this collection’s publication, Yemoja’s Tears is not subject to the standard reprint obligations of the Journal. All donated writings will be made available in perpetuity in Yemoja’s Tears in print, electronic, and audio format, as they become available. Rights to the contents donated to the anthology revert to their author six months after publication in Yemoja’s Tears. Sales of the anthology will continue to fund researched charitable clean water projects as long as the anthology is available through the publisher.

Thank you to all these talented writers for your contributions to Yemoja’s Tears, and thank you to those who purchase it for spreading hope and, with it, the opportunity to heal and thrive, with clean water.

–Novella Brooks de Vita, Acquisitions Editor-in-Chief, Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts

When Novella asked me if I would consider taking part in this project, I never could have dreamed what I was signing on for. Some of my fondest memories of the summer of 2024 involve sitting in my mother’s backyard with my laptop, sometimes so riveted by what I was reading that I forgot to edit, and had to go back and start over.

This anthology includes, among other things, informative factual pieces, breathtaking snapshots of other worlds, breathtaking snapshots of this world, keen analysis, stirring poetry, gritty space opera, haunting mystery, chilling futures, histories both idyllic and enraging, and incisive political commentary. It is, by turns, hopeful, fearful, elegiac, otherworldly, quite rightly furious, moving, and galvanizing.

It has been a magnificent honour to be part of the process of getting Yemoja’s Tears ready for publication, and I hope you enjoy it as much as I have. Authors—thank you for writing. Readers—thank you for reading!

–Cat Ashton, Production Editor-in-Chief, Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts

[Introduction: A Water Scarcity Awareness and Alleviation Anthology]

Alexis Brooks de Vita

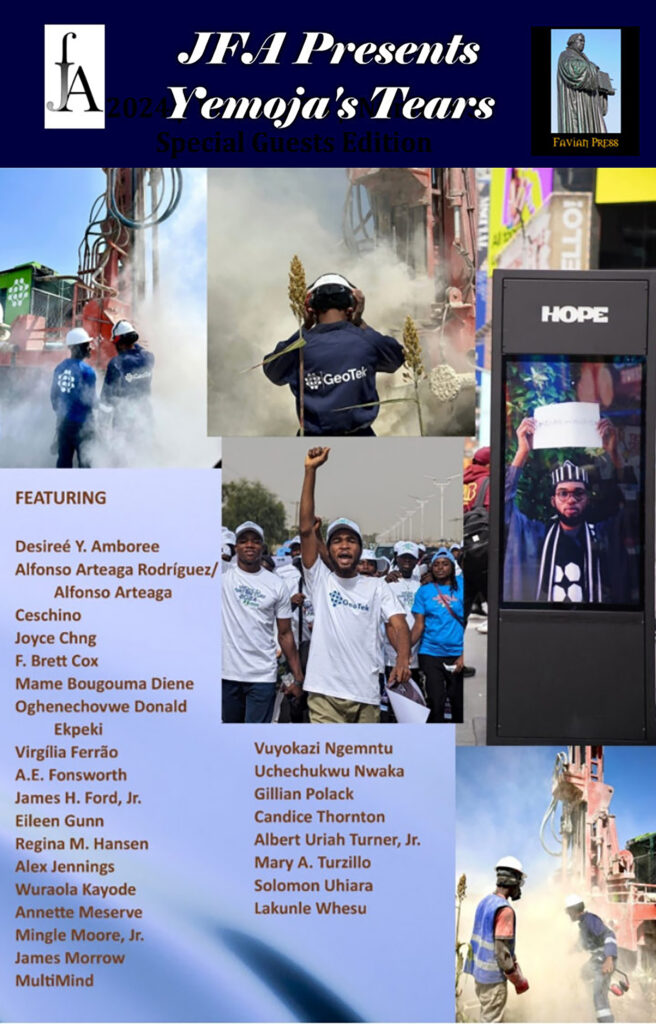

JOSHUA KEGHNEN ICHOR is a young Nigerian scientist, engineer and inventor with degrees in Hydrogeology and Environmental Science. With a background in the study of earth sciences and a strong concern for sustainable water management and environmental conservation, Ichor has invented the GeoTek Monitor, an innovation that promises to revolutionize clean water access throughout the African continent. The GeoTek Monitor provides data on water availability, quality, and usage in real time, helping communities and organizations to make informed and accurately calculated decisions about water management in the face of challenges to health and water sustainability.

Ichor’s advocacy for environmental stewardship has led to his collaboration with international research institutions and agencies concerned with water and climate resilience. His work has been awarded the Young Climate Prize, Swarovski Creative Prize, and the USADF Digital Innovation Award. Ichor is a visiting Fellow at CERN and the United States University of Africa, Nairobi, and a 776 Fellow sponsored by Alexis Ohanian through the 776 Climate Fund. Together with multi-awarded author, editor, and publisher Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki, these two young changemakers came up with the concept of Yemoja’s Tears, an anthology to both raise water scarcity awareness and to give in exchange for contributions to aid communities throughout Nigeria, the African continent, and other water-endangered areas of the world. We have researched charitable organizations that have a proven history of providing clean water to the world’s most vulnerable global communities in crisis, and have decided to begin by donating initial funds to these three: WaterAid, Water for People, and Baitulmaal, Inc.

Yemoja’s Tears: An Anthology of Water, Bodies and Bodies of Water was conceived and adopted as the first JFA Presents title by the Editors-in-Chief of the Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts. During the two years since its inception, invited authors from several continents have contributed their original water-centric works of poetry, memoirs, short stories, and essays that together immerse the reader in awareness of the threat to clean water access that is an increasingly severe danger, globally.

This anthology is rich with thought-provoking material, most of it having been years in the conceptualizing and finding of the right home. Just as Jenekacy’s front cover acrylic painting of Yemoja undersea, titled Ji, offers a vision of Afrofuturistic apotheosis, reflected by the corresponding gritty hard work in the montage of Isaac Nesla’s photos of Ichor calling for revolution while GeoTek digs for clean water south of the Sahel, so this entire anthology is a collection of aspirations, ideals, and questions reflecting light above their subsurface realities, dreads, and warnings.

Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki’s “Source” opens the anthology with hope amid images of desert and ocean, followed by the relentless interplay of shattering rock and surging sea in Mame Bougouma Diene’s “Doomed to the Storm,” wherein a crying child reminds me of a prayer that opens with “humanity is bowed down with trouble, sorrow and grief, no one escapes; the world is wet with tears,” melding fabled past and legendary future in a droughtdevastated world where one small being’s cannibalistic thirst for tears brings about a deluge. Alex Jennings’s “Stone Bridge and

Laughter” brings longing through water-carried memories of mother to the point of pathos, heightened by Candice Thornton’s “GodIsLove: Signified Sankofarrations, Personified Deities, and Mythatypical Patterns in The Joys of Motherhood and Freshwater,” analyzing the anguish of loss of the mother in the waterborne birthing of self. This equation of water with lifegiving erupts through layers of mud, myth, generation, and regeneration exquisitely simplified in Joyce Chng’s “Emerging.” Annette Meserve’s “A Pocketful of Precious” walks with a sun-scoured wanderer carrying a handful of beautiful dreams before Eileen Gunn asks the reader “Whose Water Is It, Anyway?” in flashbacks and conversations about water access, water sharing, and the combined impositions and responsibilities of the concept of rights to lifesaving water.

Solomon Uhiara demonstrates in “Bayelsa, Water for All” that water can in fact be made universally available in communities supported by their governments to achieve water equality; but this hope is challenged in F. Brett Cox’s reflective “Miriam After the Flood,” wherein a recently stable community is forced to dig itself out of the debris and detritus that remain when there are no bulwarks against the results of drastic climate change. Global regulation is needed, argues Wuraola Kayode’s “The Revenge of Yemoja,” a police procedural detecting the supernatural consequences of climate abuse, a problem simultaneously explored half a world away in Gillian Polack’s “Water Guzzlers and Time Wasters.”

“Quizani and the Eagle,” presented in both the original Spanish by Mexican poet laureate Alfonso Arteaga Rodríguez and the translation by his son, Alfonso Arteaga Martínez, follows a boy on a vision quest with the eagle who is teaching him how to mature and thrive in his threatened world, just as the heroine of James Morrow’s “The Ship of Sisyphus” plummets through layers of hierarchical privilege that the right to water consumption implies. A. E. Fonsworth’s “Ocean Scourge” likewise plunges through Earth-covering water that has been forced for far too long to absorb, cleanse and recycle the consequences of acquisitive inhumanity while Uchechukwu Nwaka’s “Inmates of Ikenga Point” sweeps readers into a breathless attempt to escape death in an abandoned prison in outer space. Will water follow the trail of humanity’s failures to nurture greed’s outcasts, its conquered, and its reviled survivors? Mingle Moore, Jr.’s sobering “Fanon and Soyinka on Traditional African Ecoharmony, Colonial Greed, and the Mystic Functionality of Water” reminds the reader that the earthly counter-balancing of fire with water has always been inevitable.

Virgília Ferrão’s “The Turning Part” questions reality and the effects of time on memory, progress, and ultimate loss, queries that Regina M. Hansen’s “Laundry” probes at a poignantly personal level. Albert Uriah Turner, Jr.’s “le mot, la mort” examines at the intersections of academia and art the traces a poet leaves to his readers, while MultiMind’s “Stalwart” smiles upon a clever inventor who challenges her society’s local politics in the face of water shortage. Water erodes the edges of memory reshaping itself in James H. Ford, Jr.’s memoir, “Finding Water to Fish with Friends and Family: Daybreak.” Mary A. Turzillo’s “Water Is Life, Water Is Death, There Is No Truth or Joy Without Water” riptides into the presence of the Queen of the Sea, decrying water abuses, pollutions, privations, and inexcusable scarcities.

Desireé Y. Amboree’s “Love, Temptation and the Downfall of a Water Rig in Kai Ashante Wilson’s ‘The Devil in America’” comes ashore in the aftermath of the war that ended U.S. chattel enslavement, where a little girl battles to protect her loved ones from supernatural malice. What may be the most dystopic of this anthology’s works, Ceschino’s “The Weird Sisters of Onapatu Bog,” wades into a cave’s eerily lit, devouring maw, where doomed heroes are forced to ponder, if water ruination and systemic pollution have not been reversed, what adaptations has Nature made?

Can the Earth, the oceans, and their denizens be healed? Have those who still have agency and opportunity sufficiently learned the lessons of ruination and embraced the sacrifices necessary for the Earth’s salvation? Culminating with Lakunle Whesu’s “Water for Tears” as a counterpoint to Diene’s crying child, and Vuyokazi Ngemntu’s “A Dry Death” mirroring Ekpeki’s “Source,” these are the questions and challenges that all the contributions to this anthology cumulatively ask and strive to help the global community of climate change survivors contemplate.