Brian W. Aldiss, O.B.E., ICFA 7, photo by Robert A. Collins

Brian Aldiss’s 1995 essay collection The Detached Retina carries a dedication to “my esteemed friends of the IAFA team,” and he goes on to name more than a dozen individuals, many of whom are still ICFA regulars or past officers. He often described ICFA as his American home, and he became the conference’s “permanent special guest” after being invited by conference founder Robert Collins to his first ICFA in 1982. A distinguished literary essayist and historian (The Trillion Year Spree: The True History of Science Fiction), as well as one of England’s great novelists and short story writers, he received the Association’s first Distinguished Scholarship Award in 1986, and in 1999–on the conference’s 20th anniversary–was finally invited as Guest of Honor. On August 19, Aldiss died at his home in Oxford, shortly after celebrating his 92nd birthday.

Brian was clearly proud of his involvement with ICFA, and his 1993 novel Remembrance Day begins with an academic conference in Fort Lauderdale that looks suspiciously familiar to anyone who attended the conference during the Fort Lauderdale years (there are even a couple of thinly-disguised sketches of IAFA folks). With his characteristically ironic sense of humor, he called his fictional academic organization “The American Stochastic Sociology Association”. He also took understandable pride in his ability to secure some of ICFA’s most distinguished guests. As he wrote in his 1998 autobiography The Twinkling of an Eye, “I have been able to invite several Guests of Honour over the years–Roger Corman for one, who came with his wife and was a winning presence. The modest Robert Holdstock also shone. Tom Shippey, long overdue, made a triumphal appearance in 1996. But perhaps the greatest success was Doris Lessing. Her sharp good humour pleased everyone.” There can be little doubt that Brian’s enthusiastic support helped cement the international reputation of the conference, helping it immeasurably to live up to its name. The very first issue of The Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts included an essay by Brian, who wanted to help the journal gain attention upon its launch.

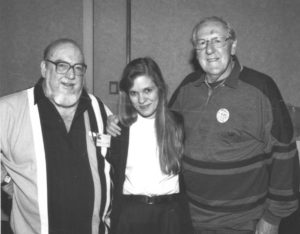

Robert A. Collins, Judith Collins, Brian W. Aldiss, O.B.E., ICFA 17, photo by David G. Hartwell

But for those who attended the conference during the Aldiss years, his unflagging energy and good humor, thoughtful and provocative participation in the academic sessions and panels, frequently hilarious readings, and original plays sometimes almost seem to overshadow his literary eminence, and the many ways in which he connected the conference to the grand traditions of fantasy and science fiction. As a young bookstore clerk in Oxford, he became friends with C.S. Lewis, who loaned a copy of Aldiss’s early novel Hothouse to his friend J.R.R. Tolkien, who wrote Aldiss a generous letter praising the work. He later became literary editor of the Oxford Mail, and eventually counted among his friends major literary figures from Kingsley Amis to Doris Lessing. He received an Order of the British Empire, a Grandmaster Award from the Science Fiction Writers of America, an honorary doctorate from Liverpool University, Hugo, Nebula, and BSFA Awards, and a special World Fantasy Award. He was a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, and an early inductee into the Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame in Seattle. His novels include not only science fiction classics like Greybeard, Hothouse, Non-Stop, and the epic Helliconia trilogy, but also more experimental works such as Report on Probability A and Barefoot in the Head and non-fantastic literary novels such as his “Squire Quartet”– Life in the West, Forgotten Life, Remembrance Day, Somewhere East of Life.

He had two major engagements with Hollywood. In 1990, the famously low-budget director Roger Corman chose an adaptation of Frankenstein Unbound for his first directorial effort after nearly twenty years (Brian showed some rather hilarious rushes from the unfinished film before the special effects had been added, with the costumed actors walking through an ordinary parking lot ). In 1982, Brian signed a contract with Stanley Kubrick–who had contacted him a few years earlier after reading Billion Year Spree, the first edition of Brian’s history of science fiction–and this led to a long and sometimes contentious series of discussions about adapting his story “Super Toys Last All Summer Long” into a film. Although Kubrick never completed the film before he died, the project was later revived by Steven Spielberg as A.I., though Brian was no longer involved.

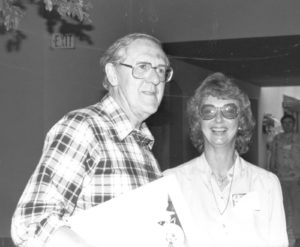

Brian W. Aldiss, O.B.E. and Sharon Baker, ICFA 3, photo by Robert A. Collins

It was easy to forget all this in light of Brian’s irrepressible antics at ICFA–dancing on the banquet tables with a young French scholar, being wheeled into a reading wearing a toga, at one point finding a thoroughly illegal way to obtain one last bottle of wine long after the bar had closed, and providing an apparently endless supply of anecdotes and memories of his experiences in Oxford, in the “Forgotten Army” during the campaign in Burma (now Myanmar) during World War II, and in science fiction; one of his funniest stories involved an unlikely and out-of-control gathering of science fiction writers in Rio in the late 1960s. There were times when Brian seemed nearly out of control as well. Surely one of the funniest performances at IAFA was his reading of a story called “Better Morphosis,” about a cockroach who wakes up one morning to find himself transformed into Franz Kafka; Brian even recruited a chorus of IAFA scholars to perform sound effects for the tale. But he was not always quite so frivolous. Some of his short plays, often performed only at ICFA, were serious business, such as his tribute to Philip K. Dick called, as I recall, “Kindred Blood in Kensington Gore”, as were most of his readings and contributions to panel discussions. One of the most enlightening debates I had ever heard about the Hiroshima bomb was between Brian–who was convinced he might have been part of the invasion of the Japanese mainland had the war continued–and the scholar H. Bruce Franklin, who had written a book arguing that the bomb partly represented America’s infatuation with superweapons.

Certainly, the many writers and scholars who first met Brian at ICFA understood his stature as a major figure in literature; many of us had been reading him since childhood. When Jane Yolen was guest of honor in 1990, Bill Senior and I had the chance to introduce her to Brian in the elevator at the Hilton; they shook hands, Brian got off at his floor, and Jane looked at us and said “I’m never washing this hand again.” That was not uncharacteristic of responses toward Brian; writers in the science fiction and fantasy fields knew they were meeting a legend, even if not all the younger attendees had grown up reading his fiction as we had. It only took a night or two of drinks by the pool to convince us that this legend was also a boon companion, a terrific raconteur, and a loyal friend not only to ICFA itself, but to many of us who got to know him there.

Brian W. Aldiss, O.B.E. and Carol McMullen Pettit, ICFA 21, photo by Robert A. Collins