Kit Reed

by Gary K. Wolfe

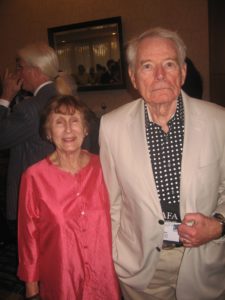

Kit Reed, ICFA 37, 2016, photo courtesy of Bill Clemente

When Kit Reed first attended ICFA in 2009, together with her husband Joe, not everyone immediately knew who she was. David Hartwell, himself a legendary editor of science fiction and fantasy who served on IAFA’s board, quickly started pointing her out to fellow board members and other attendees. “Do you know who that is?” he asked one. “That’s the legendary Kit Reed.”

David, who tragically died last year, knew virtually everyone in the field, and wasn’t easily impressed. He was not in the habit of calling anyone “legendary.” So we paid attention to this most senior of senior editors, and over the next few years Kit and Joe became not only fixtures at the conference, but dear and close friends to many of us. One of the ways of measuring the respect authors commanded, at ICFA and elsewhere, was to attend their readings. In Kit’s case, a good portion of the audience always consisted of fellow writers, clearly anxious to see what a master was up to. How did she earn such respect and affection?

For one thing, her career was simply astonishing in its consistency and longevity. One way of putting that career in context is this: when Kit published her first story in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction in 1958, David Hartwell was not yet seventeen years old. Many of the other writers who came to view her as a mentor had not been born yet. She sold stories to some of the groundbreaking editors in the field, including Michael Moorcock, Damon Knight, Avram Davidson, and Anthony Boucher, and sold other stories to publications as diverse as The Yale Review and the Village Voice. Her first science fiction novel, Armed Camps, appeared in 1969 and was among the field’s earliest critical responses to the Vietnam War. But by then she had already published three thrillers, including her first, Mother Isn’t Dead, She’s Only Sleeping. Already she had established a pattern of never quite being pigeonholed in one genre or another; in later years, she’d describe herself as “trans-genred.” As if to demonstrate, her next-to-last published novel, Where? was a classic science fiction mystery of an entire community whose residents mysteriously disappear one day, while her last, Mormama, was a Southern gothic thriller with clear supernatural elements. Her final story collection, The Story Until Now, appeared in 2013 from Wesleyan University Press and is as good a point of entry into the breadth and variety of her work as you could ask for.

Kit and Joe Reed, ICFA 32, 2011, photo courtesy of Andy Duncan

It’s no accident that Wesleyan should have published the collection, because both Kit and Joe were fixtures there long before ICFA. Their students went on not only to become not only successful writers, but to develop some of the most iconic works of recent popular culture, from Buffy the Vampire Slayer to Game of Thrones to A Series of Unfortunate Events. In 2009, those former students pitched in to pay for a labyrinth in their honor on the Wesleyan Campus. Joe himself, now retired, was a distinguished scholar of American literature and film, as well as a talented painter (one of his paintings is the dust jacket for The Story Until Now).

Nearly everyone who encountered Kit at ICFA–out by the pool bar, in luncheons or banquets, at her reading and panels–came away with stories to tell, often about her toughness, her acerbic and uncensored wit, her no-nonsense encouragement for other writers to “get back to work” or “deal with it” (which seemed, more often than not, to be exactly what they needed to hear at that point). Some of those memories and photos have been shared on Facebook by fellow writers and ICFA attendees.

Peter Straub, Kit Reed, Gary K. Wolfe, ICFA 36, 2015, photo courtesy of David G. Hartwell

I was honored to be asked to write the introduction for The Story Until Now, and in preparing it I came across an earlier essay of Kit’s, which seemed particularly appropriate regarding her approach to both literature and life. Here’s the last paragraph of that introduction, with that quotation:

Reed may take us into the minds of some decidedly unpleasant or demented characters, she may show us wars, catastrophes, dysfunctional families, werewolves, monsters, feral children, plagues, dystopias, cannibals, zombies, and weird small towns, but always with the cool yet sympathetic intelligence of an observer both outraged and wryly amused by the labyrinths we make for ourselves. Her fiction may, collectively, seem rather dark, but it may also be that by showing us the ways into these labyrinths, she’s giving us hints of the ways out as well. Reed has called this attitude “protective pessimism,” and it’s as good a phrase as any for describing the characteristic tone of her best fiction. “Dealing in worst-case scenarios doesn’t depress me,” wrote Reed in the introduction to her earlier story collection Dogs of Truth. “It makes me hopeful and resilient. Expect the worst and you’re always prepared. You scoped the exits when you came in, just in case something comes up. Something comes up and you know the quickest way out. Given a chronic imagination of disaster, I always have a Plan B.”

“This is the way lives—and stories—get built.”

Gay Haldeman, Dale Hanes, Kit Reed, Peter Straub, Joe Haldeman, and Gary K. Wolfe, ICFA 37, 2016, photo courtesy of David G. Hartwell